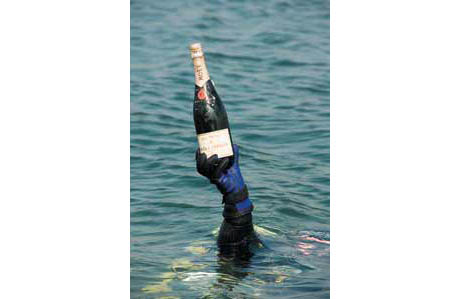

AFP reports the discovery of the world's oldest champagne in a shipwreck 55 meters deep off of the Finnish island of Aaland.

Thought to be premium brand Veuve Clicquot, the 30 bottles discovered perfectly preserved at a depth of 55 metres (180 feet) could have been in a consignment sent by France's King Louis XVI to the Russian Imperial Court.

If confirmed, it would be by far the oldest champagne still drinkable in the world, thanks to the ideal conditions of cold and darkness.

"We have contacted (makers) Moet & Chandon and they are 98 percent certain it is Veuve Clicquot," Christian Ekström, the head of the diving team, told AFP.

"There is an anchor on the cork and they told me they are the only ones to have used this sign," he said, adding that a sample of the champagne has been sent to Moet & Chandon for their analysis.

Call it the solution of a historical mystery. As usual with such things, ownership is a little bit unclear, especially since the ship seems to be within Finland's territorial waters. The Aaland authorities are meeting next week to decide who owns the find, which is potentially worth millions at auction.Aaland wine expert Ella Gruessner Cromwell-Morgan, whom Ekstroem asked to taste the find, said it had not lost its fizz and was "absolutely fabulous".

"I still have a glass in my fridge and keep going back every five minutes to take a breath of it. I have to pinch myself to believe it's real," she said.

Cromwell-Morgan described the champagne as dark golden in colour with a very intense aroma.

"There's a lot of tobacco, but also grape and white fruits, oak and mead," she said of the wine's "nose".

As for the taste, "it's really surprising, very sweet but still with some acidity," the expert added, explaining that champagne of that period was much less dry than today and the fermentation process less controllable.

"One strong supposition is that it's part of a consignment sent by King Louis XVI to the Russian Imperial Court," Cromwell-Morgan said. "The makers have a record of a delivery which never reached its destination."

Pop champagne ain't a damn thing change / Spray it in the air make it champagne rain

It's been a good couple years for ancient champagne. This week's find beats the previous record for oldest bottle of Veuve: in 2008 a Scot named Chris James found an 1893 bottle in Torosay Castle, Isle of Mull, Scotland. It had been locked in a dark cabinet along with other liquors since at least 1897. Last year there was a tasting of a bottle of 1825 Perrier-Jouet Champagne at the winemaker's cellars in Epernay. The champagne was sweeter than the contemporary version (it was topped up with brandy in the cask) but was a bit flat but with notes of "truffles, caramel and mushrooms."

Veuve Cliquot is quite important in the history of champagne. Madame Cliquot (the 'widow' or veuve in the brand name) ran the firm from 1805 to 1866 and transformed champagne from an artisanal to a mass produced product. With her staff she invented a vastly more efficient way of removing lees and yeast from the bottles (riddling) - making champagne a clear beverage for the first time. The Finnish bottles, from the 1780s, predate this transformation and represent an rare surviving example of a pre-industrial wine.

Up from the deeps!

Shipwrecked wine is not as unusual as you might think. Wine has been a widely traded commodity for, well, as long as people have been making wine (at least 7,000 years). Booze was an important part of the neolithic revolution and people have been greedy for it ever since. In other words, drinking wine is very stone age. Nicola at Edible Geography (another blog I love) has a great reflection on shipwrecked wines:

It appears the ocean floor, if treated as a single entity, might actually be the world’s largest wine cellar – a sunken treasure trove of lost vintages awaiting rediscovery. Like squirrels digging up acorns, wreck-divers and salvage companies stumble upon another forgotten cache every few years.She also points out that drinking the stuff can actually have some archaeological value:

A 1996 paper published in the Australasian Historical Archaeology journal discusses the analysis of wines recovered from an 1841 shipwreck – the William Salthouse, in Melbourne’s Port Phillip Bay – in terms of the evolution of Muscat. By combining chemical composition analysis with sensory data (i.e. sampling) and archival research, archaeologists with Heritage Victoria discovered that “Muscat was traditionally an unfortified style, quite different to today, due to a vinification technique called passerillage,” which created a wine with such high sugar levels that, to modern oenologists, it tastes like Sauternes.Not that it's much of a challenge to convince archaeologists to drink wine. In fact one might wonder why the archaeology of booze is so underdeveloped, given the rampant drinking that besets the average dig.

I'll talk about wine recovered from Greek and Roman wrecks some other time. For now I'll leave you with some other more recent shipwrecked wine links, like the 1907 Heideseck discovered in a shipwreck a few years ago (mostly covered by luxury blogs, which ironically have really bad grammar and writing!) Also check out these wines recovered from the Titanic.