Anytime there's a big historical transformation, our culture has to pick which events to remember as milestone, and figure out how to turn it into 'heritage' (by which I mean the 'official selection' of historically important places and things). The internet generation saw nerd culture rise to dominate and transform our world, which poses some odd problems for making a list of 'heritage' that needs 'protection'.

First of all, nerd spaces look like crap! They're not monumental or even especially pretty. I mean, any third-rate European castle with absolutely no historical relevance looks way better than any of the places from where the nerds have unleashed a new civilization. To demonstrate, a tour of some potential 'heritage sites' for the digital age:

Steve Jobs' garage in Los Altos, California, where he and Wozniak built the Apple I in 1976:

|

| Photo Cicorp |

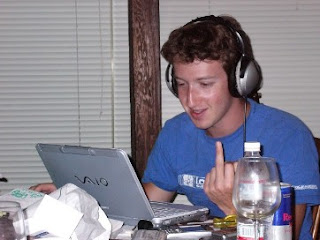

Here's Mark Zuckerberg in the early days of Facebook, surrounded by garbage and flipping the bird in his squalid Harvard dorm room:

Here's the cubicle at PayPal where YouTube got started after hours:

I want to puke just looking at these pictures. Ranch houses, dorm rooms, and cubicles: these are the paragons of American architectural mediocrity that launched a billion facebook stalkers, iphone obsessives, and cute kitten videos. But places are important, so I'm gonna calm the gag reflex and think about them. They're all modest, closed in, unremarkable, normal spaces. No surprises. Almost every American has been to one of these.

These 'heritage' places of the internet age say nothing, not power, not wealth, not authority. They were the nondescript vessels of something transformative, mute witnesses of events that their architectural surroundings were never intended to facilitate - events that their architects could not even have comprehended. Even the lamest, most irrelevant medieval castle in Europe has these places beat hands down for architectural drama.

But something different is going down here, too - the difference between the cubicle and the castle is that it's a moment of invention that's being fetishized, rather than an aesthetic system or social class. Most monuments on the World Heritage List were built to sustain these kind of ideas, in an effort to make power grabs seem like something permanent. Here's where the 'heritage' model gets kind of warped and twisted: the moments and places where something new is launched are usually pretty run down and uninspiring compared to the events that take place there. Finding a fit setting for the great stories of history is something else entirely.

UNESCO, in fact, has some ideas about preserving Internet Heritage, though a lot of it involved vapid comments like "digital heritage is likely to become more important and more widespread over time". Duh. But they're mostly talking about media, the portable stuff - not the monuments. When will the great centers of computer innovation get on the World Heritage List? Or is the strangeness of that question are an argument that the monument is dead as a cultural form?